Swift types have three properties to consider when you’re dealing with them in memory: size, stride, and alignment.

Size

Let’s start with two simple structs:

struct Year {

let year: Int

}

struct YearWithMonth {

let year: Int

let month: Int

}

My intuition tells me that an instance of YearWithMonth is larger—it takes up more space in memory—than an instance of Year. But we’re scientists here; how can we verify intuition with hard numbers?

Memory Layout

We can use the MemoryLayout type to check some attributes around how our type looks in memory.

To find the size of a struct from its type, use the size property along with a generic parameter:

let size = MemoryLayout<Year>.size

If you have an instance of the type, use the size(ofValue:) static function:

let instance = Year(year: 1984)

let size = MemoryLayout.size(ofValue: instance)

In both cases, the size is reported as 8 bytes.

Not surprisingly, the size of our struct YearWithMonth is 16 bytes.

Back to Size

Size of a struct seems pretty intuitive — calculate the sum of each property’s size. For a struct like this:

struct Puppy {

let age: Int

let isTrained: Bool

}

The size should match the size of its properties:

MemoryLayout<Int>.size + MemoryLayout<Bool>.size

// returns 9, from 8 + 1

MemoryLayout<Puppy>.size

// returns 9

Seems to work! [Narrator: Or does it? 😈]

Stride

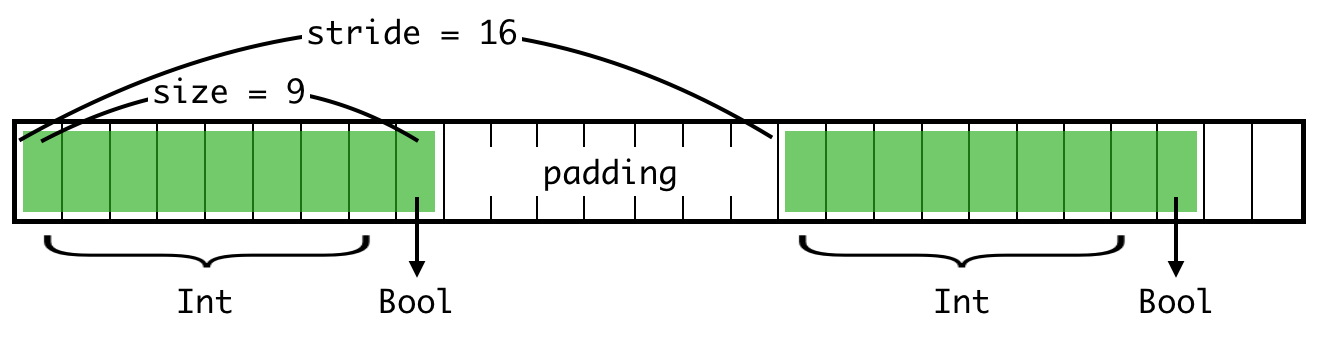

The stride of a type becomes important when you’re dealing with multiple instances inside a single buffer, such as an array.

If we had a contiguous array of puppies, each one with a size of nine bytes, what would that look like in memory?

Turns out, not quite. ❌

The stride determines the distance between two elements, which will be greater than or equal to the size.

MemoryLayout<Puppy>.size

// returns 9

MemoryLayout<Puppy>.stride

// returns 16

So the layout actually looks like this:

That is, if you had a byte pointer to the first element and wanted to move to the second element, the stride is the number of bytes distance you’d need to advance the pointer.

Why would size and stride be different? That takes us to our final magic number of memory layout.

Alignment

Imagine the computer fetched eight bits, or one byte of memory at a time. Asking for byte 1 or byte 7 takes the same amount of time each.

Then you upgrade to a 16-bit computer, which access data in 16-bit words. You still have old software that wants to access data by the byte but imagine the possible magic here: if the software asked for byte 0 and byte 1, the computer can now do a single memory access for word 0 and split up the 16-bit result.

Byte-level memory access is twice as fast in this ideal case! 🎉

Now say a rogue program put in a 16-bit value like this:

Then you ask the computer for the 16-bit word at byte location 3. The problem is the value is misaligned. To read it, the computer needs to read the word at location 1, chop it in half, read the word at location 2, chop it in half, then paste the two halves together. That’s two separate 16-bit memory reads to access a single 16-bit value — twice as slow as it should be! 😭

On some systems, unaligned access is worse than slow — it’s not allowed entirely, and will crash the program.

Simple Swift Types

In Swift, the simple types such as Int and Double have the same alignment value as their size. A 32-bit (4 byte) integer has a size of 4 bytes and needs to be aligned to 4 bytes.

MemoryLayout<Int32>.size

// returns 4

MemoryLayout<Int32>.alignment

// returns 4

MemoryLayout<Int32>.stride

// returns 4

The stride is also 4, meaning values in a contiguous buffer are 4 bytes apart. No padding needed.

Compound Types

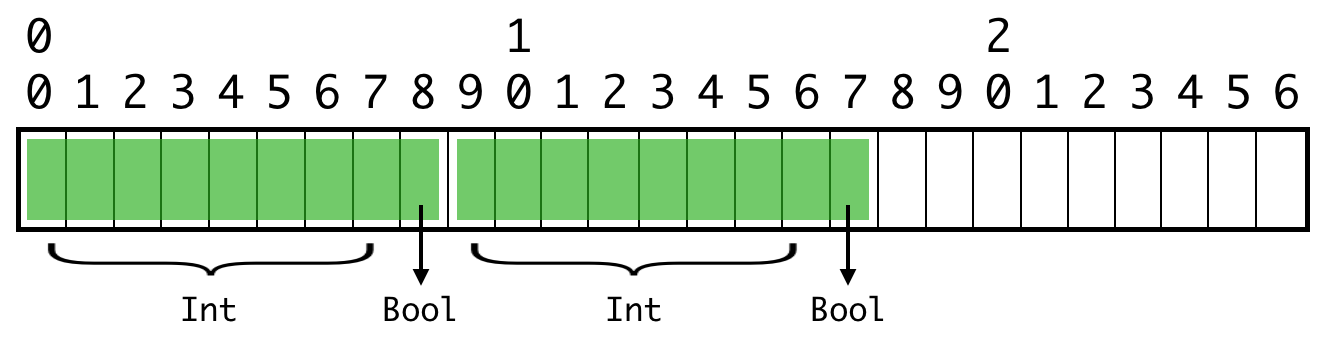

Now back to our Puppy struct, which has an Int and a Bool property. Consider again the case where values are right up against each other in a buffer:

The Bool values are happy where they are, since they have alignment=1. But the second integer is misaligned. It’s a 64-bit (8-byte) value with alignment=8 and its byte location is not on a multiple of 8. ❌

Remember the stride of this type was 16, meaning the buffer actually looks like this:

We’ve preserved the alignment requirements of all the values inside the struct: the second integer is at byte 16, which is a multiple of 8.

That’s why the struct’s stride can be greater than its size: to add enough padding to fulfill alignment requirements.

Calculating Alignment

So here at the end of our journey, what is the Puppy struct type’s alignment?

MemoryLayout<Puppy>.alignment

// returns 8

The alignment of a struct type is the maximum alignment out of all its properties. Between an Int and a Bool, the Int has a larger alignment value of 8, so the struct uses it.

The stride then becomes the size rounded up to the next multiple of the alignment. In our case:

- the size is 9

- 9 is not a multiple of 8

- the next multiple of 8 after 9 is 16

- therefore, the stride is 16

One Last Complication

Consider our original Puppy and contrast it with AlternatePuppy:

struct Puppy {

let age: Int

let isTrained: Bool

} // Int, Bool

struct AlternatePuppy {

let isTrained: Bool

let age: Int

} // Bool, Int

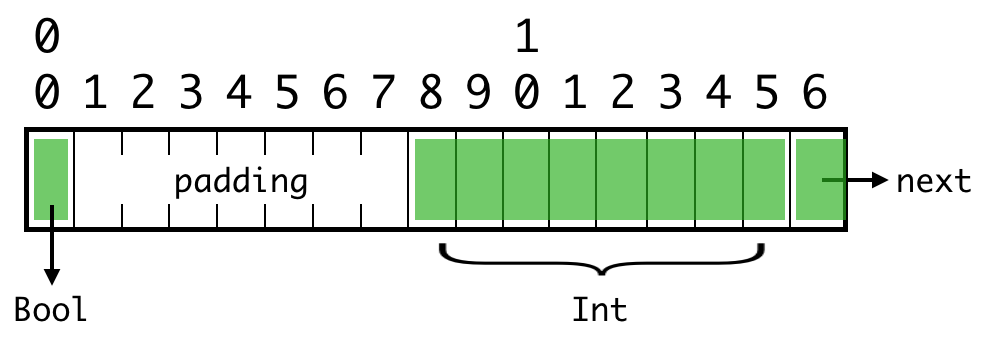

The AlternatePuppy struct still has an alignment of 8 and stride of 16, but:

MemoryLayout<AlternatePuppy>.size

// returns 16

What?! All we did was change the order of the properties. Why is the size now different? It should still be 9, shouldn’t it? A Bool followed by an Int, like this:

Maybe you see the problem here: the 8-byte integer is no longer aligned! What this actually looks like in memory is this:

The struct itself has to be aligned and the properties inside the struct have to stay aligned. The padding moves in between elements, and the size of the overall struct expands.

In this case, the stride is still 16 so the effective change from Puppy to AlternatePuppy is the position of the padding. What about these structs?

struct CertifiedPuppy1 {

let age: Int

let isTrained: Bool

let isCertified: Bool

} // Int, Bool, Bool

struct CertifiedPuppy2 {

let isTrained: Bool

let age: Int

let isCertified: Bool

} // Bool, Int, Bool

What are the size, stride, and alignment for these two structs? 🤔 (spoiler)

The Closing Brace

In the end, say you have an UnsafeRawPointer (aka a void * in C). You know the type of thing it points to. Where do size, stride, and alignment come into the picture?

- Size is the number of bytes to read from the pointer to reach all the data.

- Stride is the number of bytes to advance to reach the next item in the buffer.

- Alignment is the the “evenly divisible by” number that each instance needs to be at. If you’re allocating memory to copy data into, you need to specify the correct alignment (e.g.

allocate(byteCount: 100, alignment: 4)).

For most of us, most of the time, we probably deal with high-level collections such as arrays and sets and don’t need to consider the underlying memory layout.

In other cases, you work with lower-level APIs on the platform or interop with C code. If you have an array of Swift structs and need your C code to read it (or vice versa) you’ll need to worry about allocating a buffer with the correct alignment, making sure padding inside the struct lines up, and making sure you have the right stride value so you can interpret the data correctly.

And as we saw, even calculating size isn’t as simple as it seems — there’s some interplay between the size and alignment of each property that determines a struct’s overall size. So understanding all three means you’re on your way to being a master of memory.

Interested in reading more?

- “Data structure alignment” on Wikipedia

- “Type Layout” article in the Swift docs, explaining how to calculate size, stride, and alignment for a struct

- getAlignOf source in LLVM

- UnsafeMutableRawPointer.allocate() with size and alignment

}